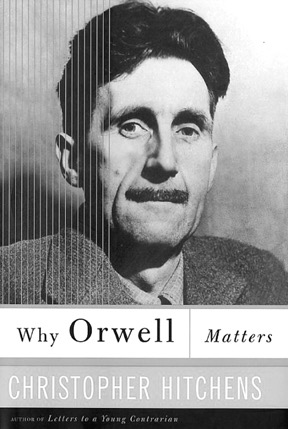

Christopher Hitchens, Why Orwell Matters (Basic Books, 2002)

As published in the Brooklyn Rail:

George Orwell matters because he not only coined the term "Cold War," but because he’s been the champion of Cold War propaganda since 1947.

Of course, despite his title, Christopher Hitchens won’t tell you that. Indeed, he makes no effort to address the question of Why Orwell Matters. More in keeping with his trajectory is the United Kingdom title, Orwell’s Victory, the imperialist boast of which Hitchens was right to suspect might not play too well in the United States.

For that matter, Orwell’s Victory probably wouldn’t have played too well with Orwell himself. To quote Benedict Nicolson in1953, Orwell "was always rounding on his own side on the eve of victory, calmly pointing out that the glorious advance was only another sort of retreat: a retreat, as he would put it, from the truth."

Certainly, Mister Hitchens can be compelling. Orwell’s weirdly immature relationship to sexuality is a featured argument of Hitchens’s text, and despite Orwell’s apparently Catholic notion of human babies (that there weren’t enough), his disdain for not just abortion but birth control, and the thinness of his estimation of women, Hitchens’s contention that Orwell may have had unresolved sexual-orientation issues makes Orwell all the more human. Hitchens also makes a helpful excursion into Orwell’s curious cluelessness as to America and American Culture. Hitchens, however, proves susceptible to this fault, with the argument that American literature began with Mark Twain. The assertion, borrowed from Ernest Hemingway, was never "uncontroversial," as Hitchens casually remarks, but intentionally perverse, and grossly exclusionary. Suffice it to say, without belaboring the insanity of the position, most of literate America would cite Washington Irving’s 1809 burlesque, The History of New York, as the start of American letters.

Of course, if any of this is why Orwell matters, he doesn’t. One has the suspicion that, aside from the occasional gaffe, Hitchens’s personal/political history of Orwell is more or less correct— and yet, to read about Orwell and the metric system, or about the hotly contested question of who hit whom with a walking stick seventy years ago, is to wonder why one isn’t doing the dishes. At such times, it feels like the predominant strategy of the Orwell defense is to bore everyone into submission.

Even Hitchens’s thesis— that Orwell "got right" the three most important issues of the twentieth century, Stalinism, imperialism, and fascism— feels weirdly outmoded. Maybe, to look singularly at the first half of the twentieth century, one could argue that those issues fill out the top three spots. But to look at the second half of the twentieth century, the win, place and show would be something more along the lines of race, religion and representation. And, looking back on the century as a whole, the most important issues would have to be food and fuel, and maybe, retrospectively, water.

For someone who speaks so beautifully, Hitchens mounts an argument for Orwell that is often shimmeringly lackluster. As Hitchens rattles off that Orwell "had dirt under his fingernails, and an understanding of the rhythms of nature," one can only groan. Most of the prose exhibits a peaty fluidity, but argument to argument, the entirety devolves. Because the majority of us, unlike Hitchens and Orwell, have not and will never be Communists, the political infighting of the Communist Party is not only toilsome and outdated, but evasive of Orwell’s perpetual-war contribution to present day dilemmas. Hitchens fails to engage the central issue— the millions of classroom copies of Animal Farm and 1984, and the impact that has had, does have, and will have, on any child who wishes to exhibit a healthy contrarian point of view.

To exhibit a revolutionary impulse, in American public schools, is to be met with brays of, "Four legs good, two legs bad."

But Hitchens, for all his talk of nuanced debate, is not concerned with such niceties. In his latest incarnation (Pinko Tory), Hitchens plays to perpetual war paranoia, tips patriotism to nationalism, and is ever on the hunt for the lowest common denominator. It is his moment of "America: like it or lump it." Dissent is unpatriotic. Even for those asking not if but how we should enter the fray, the answer is a raspy, "This is what we’re up against. Bin Ladenists." You will not hear it from Hitchens’s lips that, judging by Orwell’s stance on World War II, Orwell might have been a peacenik himself.

Hitchens’s case for Orwell is— trust the good father. First there was Alexander the Great, then there was George Orwell. They mean for the best, and will lead us to better days. No matter that America won Orwell’s "Cold War" due to a better economic model, and not the Animal Farm model of perpetual war, and the resulting arms race. No matter that in a Communist system it’s cheaper to manufacture arms, and that, very possibly, we won the Cold War despite the arms race.

For all his protestations, Hitchens is the Grand Poohbah of the cult of Orwell, and, in that capacity, it is his purview to protect Orwell from such rationality. Hitchens’s preference would be that Orwell be relegated to the past: "The disputes and debates and combats in which George Orwell took part are receding into history." This, while erasing some history, such as the unmentionable fact that Animal Farm was based on Russian Historian Nikolai Kostomorav’s story, "The Animal Riot," and, by current standards, would have faced charges of copyright infringement. In this day and age, to read "Shooting an Elephant," or The Road to Wigan Pier, is to be offended, and yet Hitchens insists, "it has lately proved possible to reprint every single letter, book review and essay composed by Orwell without exposing him to any embarrassment."

Yeah, if you ignore the parts you don’t like. Hitchens objects that Orwell’s detractors are guilty of taking Orwell’s works, acts and statements out of historical context. But, isn’t surviving historical context the challenge of literature? None of the 11 year-olds reading Animal Farm are reading it in historical context. Orwell is presently utilized to maintain an eternal enemy on the horizon. Furthermore, the questioning of Orwell is not newfangled. Prior to the publication of Animal Farm, T.S. Eliot assessed that Orwell’s pigs, in comparison to the other farm animals, were too intelligent, and thus that age-old we’re-better-than-you justification of the ruling class, and that Orwell’s allegory presented an argument so negative so as to discourage political engagement— all of which was exactly correct, and in context.

Demonstrating a consistent lack of aptitude for "the power of facing," Hitchens just dismisses the work of anyone he disagrees with. Salmon Rushdie, Edward Said, Martin Amis, etcetera— all wrong, foolish or deceitful. Hitchens’s rule is, if it’s minor, concede it, if it’s major, say it’s minor. In his hiccup of a chapter discussing the most disputed issue of the Orwell legacy, Hitchens pooh-poohs the list of 135 names that Orwell wrote up in the capacity of an informer for the "Information Research Department" (of the British Secret Service). To Hitchens, Orwell didn’t mean any harm, and probably didn’t do any harm, and the 35 names not yet released by the British government don’t indicate an obscuring of something untoward, such as a "blacklist," but rather, the "inanity of British officialdom." Of the list that has been released, Orwell’s bluntly racist, anti-Semitic and homophobic asides are similarly submitted to Hitchens’s power of sidestepping. (Throughout Orwell’s Victory, the arguments often feel so extraneous that one cannot help but suppose all the quotes in the book might be sustained, as is, to support a wholly oppositional argument.)

To Hitchens, Orwell cannot be held culpable for the list. He is, at worst, a victim of circumstance. Says Hitchens: "Sometimes his [Orwell’s] upbringing or his innate pessimism triumphed over his conscious efforts." And while Orwell "analyzed the temptation among intellectuals to adapt themselves to power," no such thought ever occurred to Orwell. In spite of the fact that Orwell numbered "sheer egoism" as number 1 on another of his lists, "Why I Write," Orwell is unfailingly without mercenary intent. While Orwell wrote that "There is no such thing as ‘keeping out of politics,’" by Hitchens’s estimation, there was never any politicking in Orwell’s decision making. (Thank heaven he flip-flopped on Hitler, anyway.) And, while Orwell "could feel the onset of the permanent war economy, and he already knew the use to which permanent war propaganda could be put," he was unconscious of the use to which his list would be put. Though a master of propaganda, he just didn’t know that they’d be using Animal Farm for that. Really.

When cornered, Hitchens always returns to the Great Man argument. This kind of thing: he was always trying, and that makes you great, and ultimately worthy of forgiveness. Orwell himself disdained the Great Writer formulation, and one needn’t go far to guess that, confronted by such Sainthood, Orwell would be inclined to point back at Hitchens. Writers, Orwell observed, "tell you a great deal about [themselves], while talking about someone else." That noted, we might find Orwell’s objection to his own canonization in his 1949 critique of Gandhi:

One may feel, as I do, a sort of aesthetic distaste for Gandhi, one may reject the claims of sainthood made on his behalf (he never made any such claims about himself, by the way), one may also reject sainthood as an ideal and therefore feel that Gandhi’s basic aims were anti-human and reactionary: but regarded as a simple politician, and compared with the other leading political figures of our time, how clean a smell he has managed to leave behind!

Faint praise, indeed. But still, if this is what Hitchens is hoping his critics will think of him (much as he writes, "Orwell kept his corner of the Cold War fairly clean"), Hitchens will leave no such air of odorlessness. Regardless of whether or not Orwell did make, or would have made, or would have recanted a turn to the right, Orwell, to Hitchens, is little more than self-justification. As much as Hitchens models himself on Orwell, one can’t dispel a notion that Orwell probably wouldn’t have liked Hitchens, either. Employing Orwell to bludgeon dissent, Christopher Hitchens has firmly positioned himself among the legions of "smelly little orthodoxies" that Orwell considered "a pox on the twentieth century."